Measuring Progress Toward Marine Conservation Goals

2020 is finally here. It’s a date that looms large in the fight to save the planet. This year marks the deadline for reaching the global target for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), to protect 10% of the world’s coastal and marine waters in effectively managed, ecologically representative, and well-connected systems of protected areas. Many countries, organizations, and individuals are eager to see if we’ve met the mark, both globally and on smaller, country or regional scales. However, this basic question can result in multiple different answers based on variations in how and when marine protection is counted.

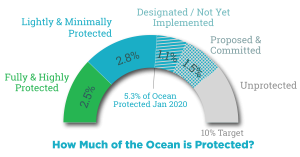

As of January 2020, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s World Database of Protected Areas (protectedplanet.net) and the Atlas of Marine Protection (MPAtlas.org), the two primary sources for global and regional marine coverage statistics, report 7.9% and 5.3% global marine coverage, respectively. Some of this discrepancy is due to inconsistency and ambiguity in the reporting of what is considered a marine protected area (MPA). For example, the World Database of Protected Areas (WDPA) collects self-reported MPA information from individual countries and utilizes this data to generate global and regional statistics. However, these widely reported statistics include some protected areas that do not meet the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) definition of an MPA, such as the perennially mis-reported Steller Sea Lion critical habitat off the coast of Alaska in the United States.

Additionally, the WDPA numbers traditionally reflect MPAs that have achieved legal designation, even if the implementation of MPA regulatory structure, enforcement, and management are lagging far behind. Full implementation (meaning that regulations are enforced on the water) can take many years. As such, this method results in the inclusion of sites that are not yet administering actual protection. In the case of very large MPAs, the time lag between designation and implementation can contribute to a large amount of prematurely reported marine protection. Areas such as the Kermadec Islands in New Zealand, Marae Moana in the Cook Islands, and the Natural Park of the Coral Sea in New Caledonia are currently held up in the implementation process and have not yet established MPA-level protections (some smaller zones might contain some management measures). These discrepancies can greatly affect the amount and type of protection reported, and they account for a large portion of the difference between statistics cited from the WDPA and the Atlas of Marine Protection reporting of 5.3% global marine protection.

Thirdly, MPAs vary widely in their goals and regulations, which in turn, impacts expected and realized conservation outcomes. For example, a marine area may be termed an ‘MPA’ but place no restrictions on some or all destructive activities, resulting in little positive environmental change. The broadly reported WDPA numbers do not differentiate the variation in protection levels among the reported MPAs. The team at Atlas of Marine Protection independently verifies these regulatory differences and reports only 2.5% of the world’s oceans are within MPAs that prohibit significant levels of human extraction and fishing through what is called “no-take” marine protected areas.

So… what really is an MPA?

As a whole, this series of discrepancies is significantly hindering our ability to accurately track marine protection and record progress toward international conservation goals. Inconsistent reports and overestimations of progress can obscure real change and distract attention from the overarching goal of sustaining a healthy ocean and conserving biodiversity. It’s increasingly clear that the solution lies in a standardized definition of afforded protections that qualify as an MPA and contribute to the conservation of biodiversity, as opposed to ‘paper parks’ or minimally protected areas (i.e., that do not restrict some or all destructive activities).

As such, members of the marine community, led by Oregon State University (OSU), Marine Conservation Institute, and WDPA are collaborating on The MPA Guide, an effort to standardize the definitions and criteria utilized in discourse surrounding marine protected areas and measuring our progress toward international conservation goals. Throughout 2020, our team at the Atlas of Marine Protection will help identify and train ‘early adopter’ countries to apply these criteria to existing marine protected areas. This data will allow us to more accurately measure and recognize progress toward conservation goals by distinguishing highly and fully marine protected areas that effectively reduce or prohibit impacts from extractive human activity from those with less stringent protection.

Accurate and unified reporting of MPA numbers will be crucial as the global community moves towards increased levels of marine protection in the next decade while the effects of climate change and political upheaval take hold. The UN is also expected to announce a new legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction, which is the first step in meaningful protection on the high seas. It is an exciting time in marine conservation because the time to take bold action is now, and there is hope that the next decade might help alter the trajectory of a rapidly changing ocean.

from On the Tide https://ift.tt/2OoTEKF https://ift.tt/37YilFE

No comments:

Post a Comment